April 11–17 marks Black Maternal Health Week, a time dedicated to acknowledging the unique experiences Black birthing people face before, during, and after pregnancy. While the data around the inequities is well known — Black maternal mortality rates are nearly triple that of white parents — these numbers only provide a high-level view. Each pregnancy is different, and each number represents real families.

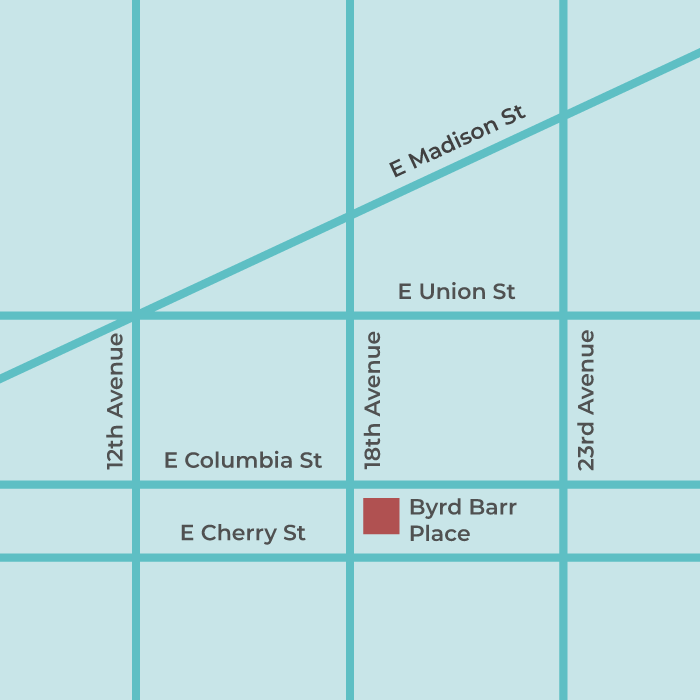

We sat down with three Black mothers at Byrd Barr Place, Dr. Angela Griffin, Rosie Grant, and Lanek Hampton to hear about their journeys to motherhood and their experiences navigating the healthcare system as Black women.

Understanding inequities in health care

With six pregnancies between them, the women shared common themes, particularly around challenges in being heard and getting adequate care, as well as the importance of self-advocacy in a system that too often fails Black women.

Angela’s four pregnancies were all different. Her first child was easy, her second delivery required more serious medical interventions due to her daughter’s position in the womb. During her third pregnancy, Angela escalated her concerns to the chief of hospital after receiving inadequate care for preeclampsia, a serious condition that affects Black women 60% more than white women. “I have always been a natural activist and advocate. When I sensed something was not right, that I was not getting what was due to me, I worked to get to the people who make the decisions to create the change that I and others needed,” said Angela.

Rosie’s pregnancy and delivery were colored by her intersecting identities. “They put me in a box, not only as a Black woman, but also as a bigger woman. I felt like they only saw me as a collection of stereotypes and not an individual,” said Rosie. While pregnant, she developed high blood pressure, and was treated as high risk. In addition, Rosie learned she had large fibroids, each weighing over a pound, a condition that is also seen at disproportionate rates in Black women.

During delivery, Rosie felt unheard as her wishes to be put under anesthesia for an unplanned C-section were challenged. It wasn’t until the anesthesiologist failed to give her a successful epidural, which he blamed on her for her weight, that Rosie’s request was finally honored. Due to the failed epidural, Rosie developed extreme swelling, gaining 30 pounds in water weight during the seven days she spent in in-patient care. “I was devastated. I had worked hard throughout my pregnancy not to gain excessive weight, so to have this happen was extremely discouraging,” Rosie shared.

Lanek described her pregnancy as deeply traumatic. She became pregnant during the COVID pandemic, so medical providers, especially BIPOC providers, were scarce and stretched thin. Worse still, Lanek developed hyperemesis gravidarum, a debilitating condition that causes extreme vomiting. Pregnant with twins, Lanek lost 30 pounds and became severely anemic.

As physically trying as the pregnancy was, Lanek shared that the worst part was the treatment by her medical providers. “Everyone treated me as if I was the problem, not the condition that I had,” she reflected. “The whole time the doctors were very dismissive. I found myself feeling really small. I kept thinking, ‘Why doesn’t this matter to anyone else?’”

Knowledge and advocacy — the difference between life and death

Across their varied experiences, all three women stressed the importance of being well-informed and having an advocate present.

While Angela did have a midwife during her pregnancies, when asked what she would do differently, she said that being more informed about all the options available to her, including the potential presence of a doula, could have improved her experience. “I didn’t know enough about preeclampsia and the various conditions that can impact pregnancy and birth, especially for Black women. I only knew about midwives because my grandmother literally was not allowed to give birth in a hospital, and relied on midwives to ensure a healthy delivery,” said Angela.

Rosie agreed on both points. “I would advise any potential parent to talk to the women in their family to understand their health and pregnancy experiences. In my case, it turned out that all the women on both sides of my family have fibroids.” Equally important is the need for an advocate like a doula or midwife. “A doula or midwife comes with a wealth of knowledge, and can keep providers aware and accountable to the parent’s wishes that have been written out beforehand under the doula’s care,” Rosie reflected.

Mid-pregnancy Lanek had to change doctors and her experiences were wildly different between them. Her first doctor was a Black woman who Lanek credits with giving her excellent care. “She made sure I understood everything about my experience, guided me through the statistics, and was willing to order the tests I requested,” Lanek shared.

However, after switching doctors, Lanek’s care suffered. When asked what advice she would offer potential parents, Lanek stressed the importance of having a medical provider who can empathize with one’s experience. “Never have a doctor who you feel weird or uncomfortable around. Having a doctor who has lived in your shoes makes all the difference.”

An equitable future for Black parents

In an equitable future, Black parents have the information, care and advocacy needed for healthy families.

For Lanek, an equitable future starts with honoring the humanity of Black mothers, “I think people forget that because mothers are carrying something precious that they need nurturing as well. At the end of the day, the mother is a person too, who deserves space and grace to be comfortable and deeply cared for.”

Rosie emphasized, “This is a precarious time, women are losing their rights left and right. Folks want us to have these babies, but are unwilling to take care of us while we are growing these children. It is absolutely essential for Black women to have access to midwives and doulas who are trained to advocate for us. We are always stronger together.”

Angela underscored that Byrd Barr Place plays a role in advocating for an equitable future, “It is important to tell these stories. It is through our collective experiences that we will see the necessary changes to combat Black maternal mortality and make the systemic changes required to ensure that all mothers, regardless of their identities, are empowered, healthy, and thriving.”